We can determine the chemical composition of distant gases by analyzing their light spectra, and we can even distinguish between isotopes of a single element within such a gas. We can for instance distinguish deuterium from regular hydrogen.

Light spectrum

This is because gases don’t emit light in a continuous spectrum from red to blue. There are specific energies for which gases absorb and emit light. The pattern is distinct and unique for every element in the periodic table, provided it is in its gaseous form. The shape of a light spectrum reveals in this way the chemical composition of distant gases.

If the light spectrum of such a gas is shifted towards the red, we have what we call redshift. If it’s shifted towards the blue end, we have blueshift.

The shape of a light spectrum is determined by chemical properties only, so the various isotopes of an atom all yield the same shape. They are only distinguished by their relative blueshift, where heavier isotopes of an atom emit bluer light than their lighter counterparts.

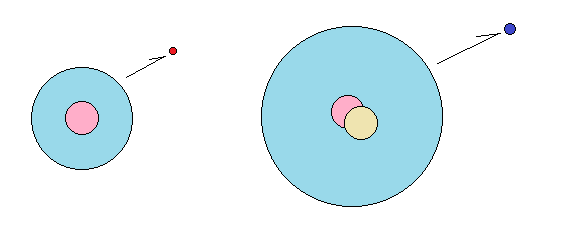

Light spectrum of deuterium

In the case of hydrogen, deuterium has a neutron attached to its nucleus. It’s therefore twice as massive as regular hydrogen, which has a sole proton in its nucleus. Chemically, the two isotopes are identical. However, their light spectra can be used to tell them apart.

Deuterium can be identified by the blueshift in its spectrum. It’s shifted towards the blue end of the spectrum by about 2 angstrom. This is how we know that the water in the tails of comets are rich in deuterium, and therefore not the source of water on our planet, which contains little deuterium.

Conclusion

All of this can be confirmed in a laboratory. The heavier the atomic nucleus is for a given element, the bluer is its light spectrum.

Halton Arp’s premise about light spectra and the mass of atoms is therefore correct.

Comments (0)